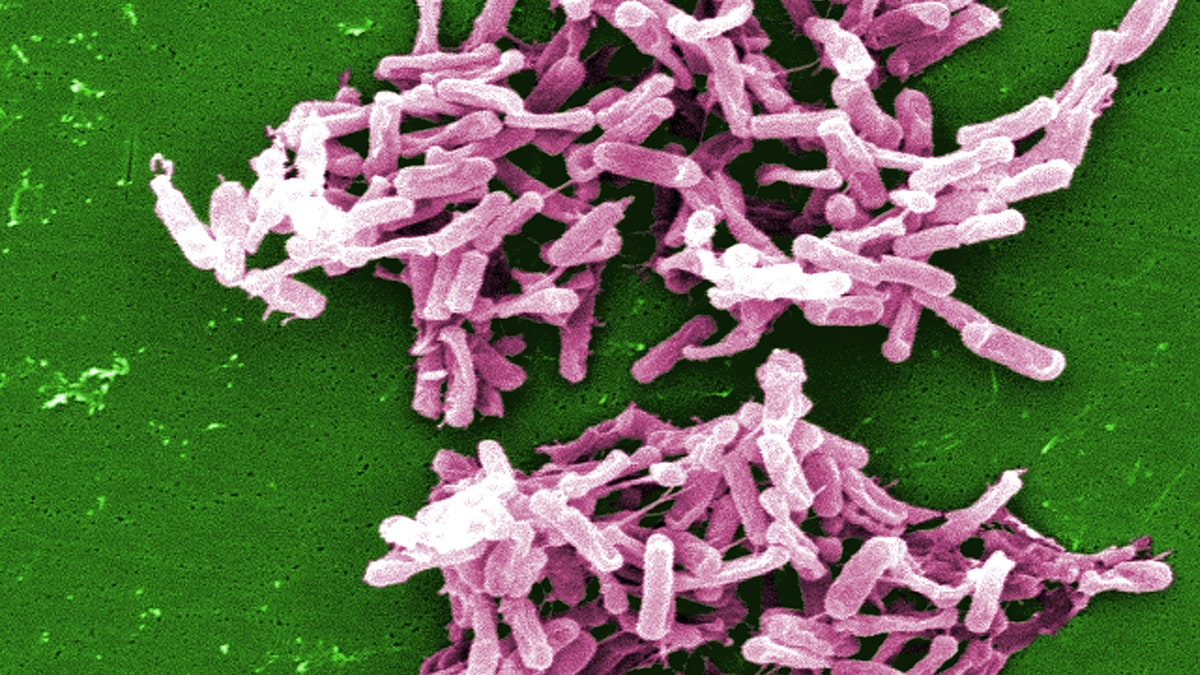

This micrograph depicts Gram-positive C. difficile bacteria from a stool sample culture. (CDC.gov)

In people who become infected with the difficult-to-treat gut bacteria called C. diff, the infection often comes back after treatment. But a new study suggests a way to ward off future infections: Give patients a nontoxic strain of the same bacteria that is causing the infection.

The study involved 173 patients who had recently recovered from infection with Clostridium difficile after treatment with antibiotics. The gut bacterial infection can cause severe diarrhea and is linked with about 29,000 deaths in the United States each year.

The bacteria make people sick because they produce toxins that attack the lining of the gut, according to the Mayo Clinic. But not all strains of C. difficile produce toxins; some lack the genes needed to generate toxins, and these bacteria can live in people's guts without causing symptoms.

In the new study, patients received a liquid containing either a nontoxic strain of C. difficile, which they took regularly for one to two weeks, or a placebo, which was taken regularly for two weeks.

About 30 percent of the patients who received a placebo developed another C. difficile infection within six weeks, compared with just 11 percent of patients who received the nontoxic strain, the researchers found. [5 Ways Gut Bacteria Affect Your Health]

The outcome was best when the nontoxic strain actually colonized the patients' guts, meaning that the nontoxic strain actually started living in these individuals' guts, along with their normal gut bacteria. Among patients who became colonized with the nontoxic strain, just 2 percent experienced a recurrent infection, compared to 31 percent of patients who received the nontoxic strain but were not colonized. (About 70 percent of all patients who received the nontoxic strain were colonized with the bacteria.)

In addition to reducing people's risk of a recurrent infection, "colonization [with the nontoxic strain] appeared to eliminate toxigenic C. difficile, which could reduce risk of C. difficile transmission in high-risk environments such as hospitals and nursing homes," the researchers, from the Edward Hines Jr. VA Hospital in Illinois and Loyola University Chicago, wrote in the May 5 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

It's not known exactly how the nontoxic strain prevents future infections with C. difficile. But it's most likely that the nontoxic strain occupies the same niche in the gut as does the toxic C. difficile and, "once established, is able to outcompete resident or newly ingested toxigenic strains," the researchers said.

It's likely that colonization with the nontoxic strain is temporary, so protection is likely not long lived, the researchers said. However, "loss of colonization presumably occurs as a result of restoration of the normal microbiota, which may then provide protection against subsequent [infection]," the researchers said.

The study also found that treatment with the nontoxic strain appeared to be safe. The only adverse event that occurred more often in patients receiving the nontoxic strain as opposed to the placebo was headaches, and this reaction was considered unrelated to the treatment in most cases, the researchers said.

There is a risk that the nontoxic strain could, in theory, acquire the genes needed to produce toxins while living in a person's gut. (Researchers have been able to transfer genes from toxic bacteria to nontoxic bacteria in a lab dish.) This means it would be important to try to eliminate C difficile infection with antibiotics first, before starting a person on treatment with a nontoxic strain.

Because the new study was small, the findings should be confirmed in larger studies, the researchers said.

- 6 Superbugs to Watch Out For

- 7 Devastating Infectious Diseases

- Tiny & Nasty: Images of Things That Make Us Sick

Copyright 2015 LiveScience, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.