NEW YORK – A surge in baby boomers has driven up the number of elderly people abusing drugs or alcohol, bringing more attention to the sometimes-delicate problems involved in treating addiction in the aging.

Last summer, the Jewish Home Lifecare nursing home in the Bronx set out to address those issues. Patients 60 and older who come in for rehab after a hospital stay are also screened for addiction and offered a chance at recovery.

Eight beds have been set aside to start, and the nursing home expects to get 480 patients a year. Associate Administrator Gregory Poole-Dayan believes it's the first nursing home to integrate addiction recovery into medical rehabilitation to reach addicts who might not otherwise seek help.

Experts said a focus on elderly addicts is increasingly needed as the population grows. A 2009 study in the journal Addiction found that because of the large size "and high substance abuse rate" of the baby-boom generation, the number of Americans over 50 with abuse problems was expected to reach 5.7 million by 2020, double the 2006 figure.

Clare Mannion, 64, of Fort Myers, Florida, says her fear of aging triggered her alcohol addiction.

"For me, growing older was not a positive thing," she said. "When life became difficult for me, when it appeared that my prejudice about being a boomer or elderly became insurmountable, I turned to the quickest, easiest, legal medication I could find."

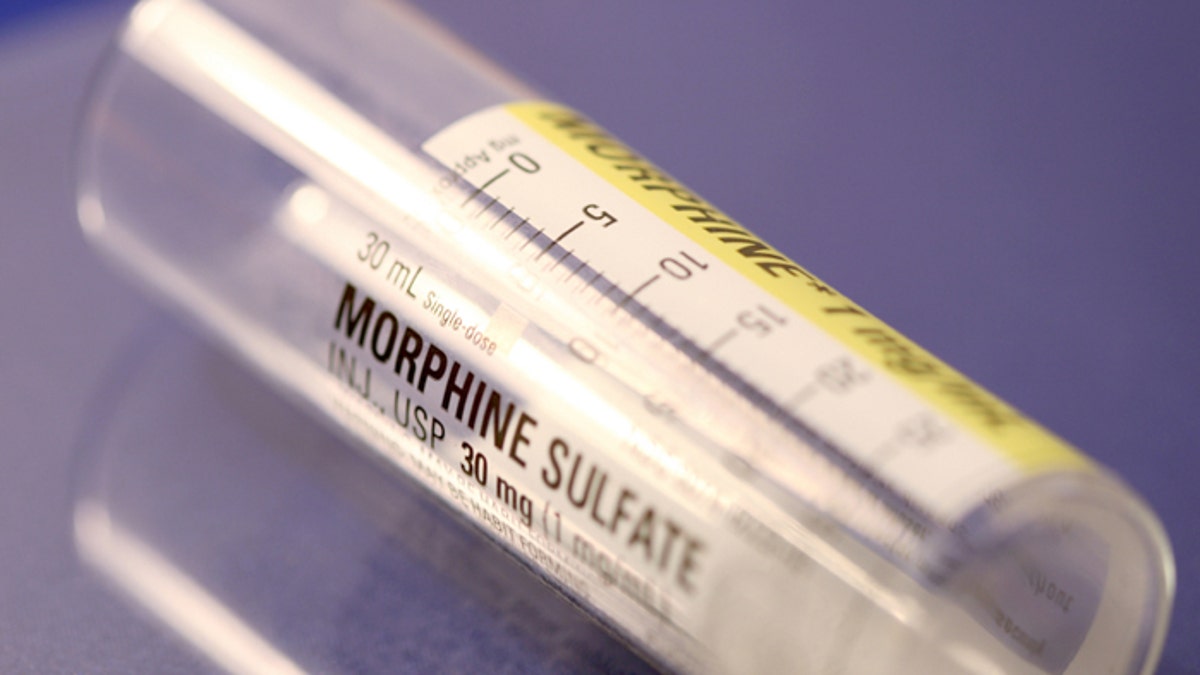

The elderly often need powerful pain medications, which are easy to overuse. They typically have dramatic changes in their personal life, such as retirement or the death of a spouse, that can trigger abuse. Family, friends and even doctors sometimes mistake the symptoms of addiction for the symptoms of old age. And dementia can both mask and worsen the effects of drugs and alcohol.

"If you look at the demographics of our country, the baby boomers are getting older and a lot of them were involved in drugs and alcohol back in the `60s and `70s," said James Emery, deputy director of the ElderCare program at the Odyssey House addiction recovery agency in Manhattan.

"Even those who were not, a lot of them have been prescribed a lot of narcotics for pain they might have from a back injury or something going on with their knee and they become addicted," he said.

The increase is a matter of demographics, Poole-Dayan said.

"We know the boomers are coming and there are going to be more and more in the future," he said. "We also know that in this society, their children are spread all over the country, so they don't come for dinner and they don't see the vodka bottle."

Alcoholics Anonymous has long offered special help to the elderly, holding meetings in nursing homes, offering transportation to frail members or even bringing meetings to the homebound. Odyssey House has residential and outpatient treatment for elderly addicts, Emery said. The Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation has an addiction treatment "track" in Naples, Florida, called BoomersPlus.

Mannion voluntarily spent seven months in BoomersPlus after a couple of DUI arrests. All the addicts were 50 or older.

"I probably could have dismissed a 20-year-old, or a meth addict, but when you're looking at other professionals - doctors, lawyers, salesmen - it's easier to acknowledge you have this disease if they're saying they have it," she said.

The new Jewish Lifecare program combines physical, occupational and psychological therapy with counseling. In the past, patients would have surgery and rehab, then go home with their physical problem addressed but their addiction untouched, Poole-Dayan said.

The program, funded by a $213,000 grant from Fan Fox & Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, is headed by Steven Wollman, a specialist in addiction and mental health. A former pain-medication addict, Wollman said Narcotics Anonymous "saved my life."

Because of that experience, "I understand what you will do to deal with pain," he said. "I also know how important support is."

Patients discharged from hospitals to the nursing home for medical rehab stay an average of only 23 days - and Medicaid won't pay for addiction care beyond medical care, Poole-Dayan said. So "the discharge plan is extremely important," he said.

A recovering addict's plan could include putting a support team in place, arranging transportation to AA or having a visiting nurse keep an eye out for signs of relapse like liquor bottles in the recycling, Poole-Dayan said.

Wollman said six of the first seven patients to go through the program are doing well and the seventh is "struggling to remain sober."

Robyn Stone, an executive director at LeadingAge, an association of geriatric care organizations, said she hopes the Jewish Home program will turn out more staffers trained in dealing with addiction. And Poole-Dayan said he hopes the program will be copied elsewhere.

"We shouldn't be the only ones doing this," he said.