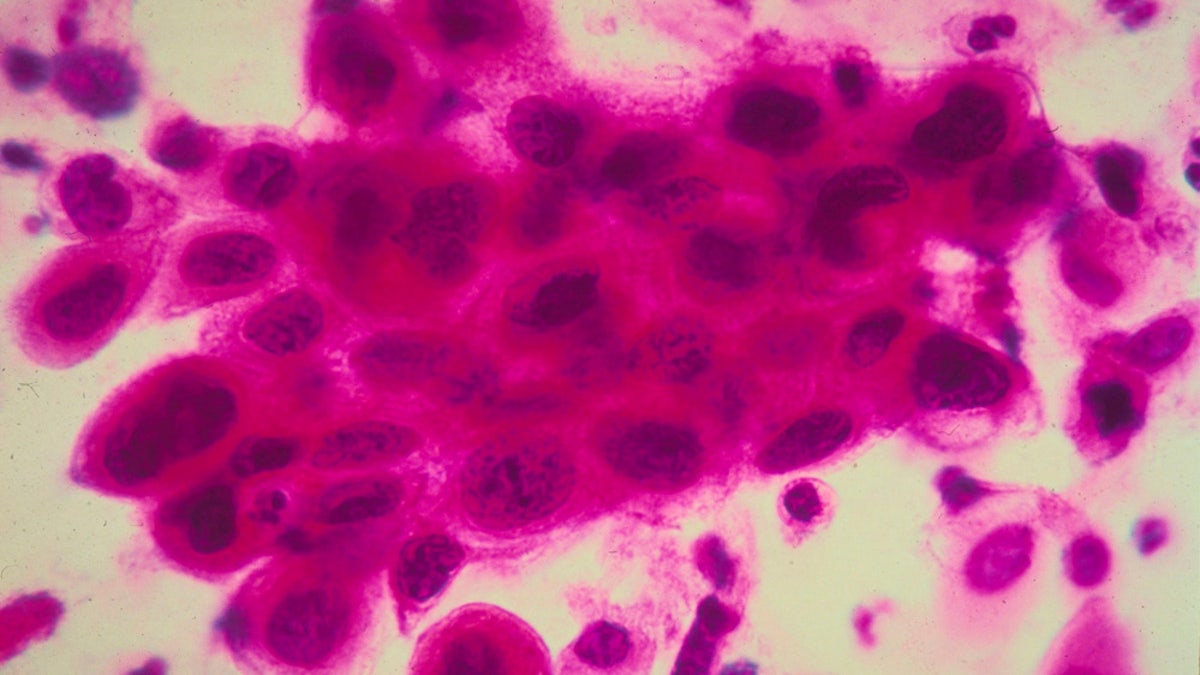

Close up of cancer cells in the cervix. Cancer of the uterine cervix, the portion of the uterus that is attached to the top of the vagina. (Photo by American Cancer Society/Getty Images)

Testing for human papillomavirus (HPV) may be the best way to know whether a woman is at risk of developing cervical cancer in the near future, according to a new study.

Negative HPV tests provided women with more reliable assurance that they wouldn’t develop cancer or other abnormal cervical changes in the next three years, compared to traditional Pap tests, researchers report.

“Primary HPV screening might be a viable alternative to Pap screening alone,” said Julia Gage, the study’s lead author from the National Institutes of Health’s National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Maryland.

About 12,000 U.S. women were diagnosed with cervical cancer in 2010 and about 4,000 died from the disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Roughly 91 percent of cervical cancers are thought to be caused by HPV.

Pap smears, which require doctors to collect cells from the cervix to look for abnormalities, have traditionally been used to determine whether a woman is at risk of developing cancer in the near future.

In 2012, the government-backed U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended women between ages 21 and 65 years be screened using a Pap test every three years and said those ages 30 to 65 years could instead opt for cotesting, which is a Pap test in combination with a HPV test, every five years.

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection and affects both men and women. About 79 million people have the infection but most people don’t know they’re infected because symptoms are uncommon.

HPV testing also requires doctors to collect cells like they would during a Pap test but the end result is whether the woman has the virus - not abnormal cells.

“What we wanted to see is whether primary HPV screening could be a good alternative to Pap and compare it to cotesting,” Gage said.

For the new study, the researchers used data from over one million women who were between ages 30 and 64 years and screened for cervical cancer at Kaiser Permanente Northern California since 2003.

The researchers followed women who had a negative Pap or HPV test to see whether they developed cervical cancer during the next three years. They also looked at how many women developed cervical cancer in the five years following cotesting.

Overall, about 20 women out of 100,000 developed cervical cancer in the three years following a negative Pap test. That compared to 11 women out of 100,000 who developed the cancer during the three years after receiving a negative HPV test.

About 14 women out of 100,000 developed cervical cancer in the five years following negative cotests, according to results published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Gage said the findings were not surprising, since HPV is the cause of most cervical cancers.

She cautioned that the results do not foreshadow the death of Pap smears. The tests may still have a role in monitoring whether women with HPV, who are at an increased risk of cancer, go on to develop abnormal cervical cells.

“We always have to reconsider how we’re screening patients and focus on the best way to screen for certain cancer,” said Dr. Mario Leitao Jr., a gynecological surgeon at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

“I think this is very interesting because instead of doing (Pap tests) every three years you could do HPV (tests) every three years,” said Leitao, who was not involved with the new study.

He said there will be a lot of variables in deciding which test is best for women.

“The best way to do it is still to be determined but it’s important they have some form of cervical cancer screening at least every three years,” Leitao said.

He added that women also have to be their own advocates and tell their doctors that they don’t need Pap tests every year.

“It shouldn’t be done more frequently than every three years,” he said.