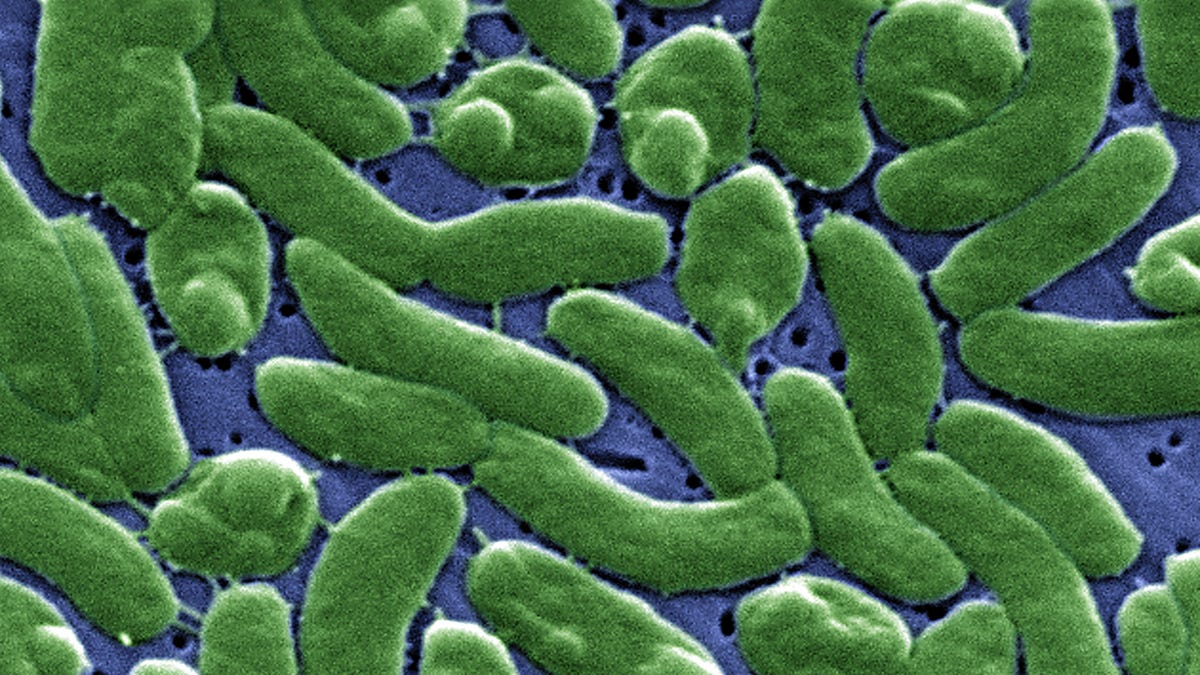

Vibrio vulnificus is a bacterium in the same family as those that cause cholera. It normally lives in warm seawater and is part of a group of vibrios that are called "halophilic" because they require salt. (CDC.gov)

Patty Konietzky thought the small purple lesion on her husband's ankle was a spider bite. But when the lesion quickly spread across his body like a constellation, she knew something wasn't right.

After a trip to the hospital and a day and a half later, Konietzky's 59-year-old husband was dead.

The diagnosis: vibrio vulnificus, an infection caused by a bacteria found in warm salt water. It's in the same family of bacterium that causes cholera. So far this year, 31 people across Florida have been infected by the severe strain of vibrio, and 10 have died.

"I thought the doctors would treat him with antibiotics and we'd go home," said Konietzky, who lives in Palm Coast, Fla. "Never in a million years it crossed my mind that this is where I'd be today."

State health officials say there are two ways to contract the disease: by eating raw, tainted shellfish -- usually oysters -- or when an open wound comes in contact with bacteria in warm seawater.

While this could potentially concern officials in a state with hundreds of miles of coastline and an economy dependent on tourism, experts say it's nothing that most people should worry about. Vibrio bacteria exist normally in salt water and generally only affect people with compromised immune systems, they say. Symptoms include vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain. If the bacteria get into the bloodstream, they provoke symptoms including fever and chills, decreased blood pressure and blistering skin wounds.

But there's no need to stop swimming in the Gulf of Mexico, says Diane Holm, a spokeswoman for the state health department in Lee County, which has had a handful of cases that included one fatality this year.

"This is nothing abnormal," she said. "We don't believe there is any greater risk for someone to swim in the Gulf today than there was yesterday or 10 years ago."

There have been reports this year in Gulf states of other waterborne illnesses, but they are rare. In fresh water, the Naegleria fowleri amoeba usually feeds on bacteria in the sediment of warm lakes and rivers. If it gets high up in the nose, it can get into the brain. Fatalities have been reported in Louisiana, Arkansas and in Florida, including the August death of a boy in the southwestern part of the state who contracted the amoeba while knee boarding in a water-filled ditch.

Dr. James Oliver, a professor of biology at the University of North Carolina in Charlotte, has studied vibrio vulnificus for decades. He said that while Florida has the most cases of vibrio infection due to the warm ocean water that surrounds the state, the bacteria is found worldwide, generally in estuaries and near the coast.

"It's normal flora in the water," he said. "It belongs there."

The vast majority of people who are exposed to the bacteria don't get sick, he said. A few people become ill but recover. Only a fraction of people are violently ill and fewer still die; Oliver said many of those people ingest tainted, raw shellfish.

Oliver and Florida Department of Health officials say people shouldn't be afraid of going into Florida's waters, but that those with suppressed immune systems, such as people who have cancer, diabetes or cirrhosis of the liver, should be aware of the potential hazards of vibrio, especially if they have an open wound.

Holm said nine people died from vibrio vulnificus in Florida in 2012, and 13 in 2011, so this year's statistics aren't alarming. What's different, she said, was that victims' families are speaking to the news media about the danger.

Konietzky watched as her husband Henry "Butch" Konietzky died on Sept. 23. She said she feels it's her mission to let others know about the potential risks. Next week, she and her husband's adult daughter are scheduled to appear on "The Doctors" television program to discuss the disease.

"We knew nothing about this bacteria," she said. Never mind that both she and her husband grew up in Florida and have spent their lives fishing and participating in other water activities.

The couple had gone crabbing on the Halifax River near Ormond Beach on Sept. 21, she said. Her husband first noticed the ankle lesion in the middle of that night. He didn't wake his wife, but in the morning, told her that it felt like his skin was burning near the lesion. Patty Konietzky took a photo of it and hours later, when her husband said he was in pain and the lesions had spread, they went to the emergency room.

Konietzky said her husband didn't have any health problems or open wounds that she knew of, and when doctors told her that he had an infection in his bloodstream, she didn't think it was too serious. Within hours, her husband's skin turned purple and it "looked like he had been beaten with a baseball bat."

Nearly 62 hours after he was in the water, Butch Konietzky died. His wife notes that she, too, was in the same water -- yet wasn't infected.

To walk around in the water and doing the things we did, you didn't give it any thought," she said.

Konietzky said her husband wouldn't want her -- or anyone else -- to stop fishing or enjoying outdoor activities because of a fear of the bacteria. Nonetheless, She wants people to be aware of the risk and is pushing her local county commission to post signs warning folks about the bacteria.

"I'm not going to be afraid of it," she said. "I have to personally put some meaning on the loss of my husband. And speaking out is all I can do."