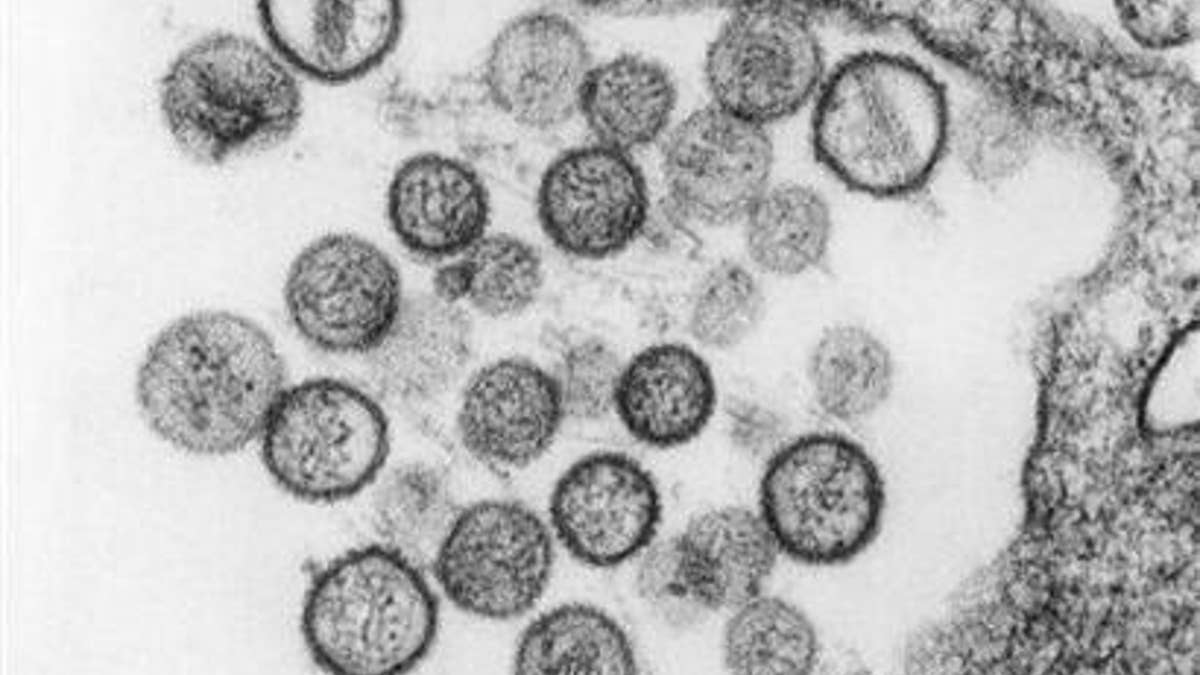

In this undated handout from the Centers for Disease Control image library, this transmission electron micrograph (TEM) reveals the ultrastructural appearance of a number of virus particles, or âvirionsâ, of a hantavirus known as the Sin Nombre virus (SNV). REUTERS/Cynthia Goldsmith/CDC/Handout

Yosemite National Park has begun trapping and killing deer mice whose growing numbers may have helped create the conditions that led to a hantavirus outbreak that has infected eight park visitors, killing three, public health officials said on Tuesday.

Yosemite officials in recent weeks have warned some 22,000 people who stayed in the park in California over the summer that they may have been exposed to the rodent-borne lung disease, which kills over a third of those infected.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has also sounded a worldwide alert, saying visitors to the park's popular Curry Village lodging area between June and August may be at risk. Park officials have closed nearly 100 tent cabins in Curry Village infested with deer mice, which carry the virus.

"From an ecological perspective, it appears that there was an unnaturally high population of rodents in the area. We are being proactive and reducing the population," Danielle Buttke, a veterinary epidemiologist for the National Park Service, told Reuters.

Buttke said the mice were being trapped in several areas of the park for monitoring purposes but believed they were being killed only in the Curry Village area, using snap traps.

Seven of the eight people confirmed to have been infected are believed to have contracted the virus in the village, while one stayed elsewhere in the park.

Public health officials trapped three times as many deer mice in the park's Tuolumne Meadows last week than were caught in a 2008 period, indicating that the deer mice population has grown, said Dr. Vicki Kramer, chief of vector-borne diseases at the state Public Health Department.

Dr. Charles Chiu, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, said the growing deer mice population might help explain the outbreak.

No cure

"This could be an explanation for why we're seeing this particular cluster," Chiu said. "What you may have is the perfect storm of conditions: increasing prevalence of deer mice and campers with the same or common exposure to (lodging) infested with deer mice."

Officials are concerned that more Yosemite visitors could still fall ill because the virus can incubate for up to six weeks after exposure. There is no cure for the syndrome but early detection and hospital care increase survival rates.

The virus can lead to severe breathing difficulties and death. Early flu-like symptoms include headache, fever, muscle aches, shortness of breath and coughing.

Last month, authorities began trapping rodents in Yosemite to examine whether deer mice there were more likely to be infected with the hantavirus than deer mice elsewhere, Buttke said, but found they were not.

When authorities first identified the Yosemite hantavirus outbreak, rangers balked at the idea of trying to exterminate the deer mice, arguing that the mice play an important role in the Yosemite ecosystem.

But when they realized the deer mice population had swelled, they decided to thin it in an effort to rebalance the ecosystem, Buttke said. She theorized that weather combined with visitors bringing in food led to Yosemite's abundance of deer mice.

Deer mice release hantavirus in their urine and droppings. People can contract the virus when they breath contaminated air. Children rarely contract the virus, probably because it is often transmitted when adults sweep or vacuum droppings or cut and stack wood.

People usually contract the virus in small, confined spaces with poor ventilation. They also can become infected by eating contaminated food, touching tainted surfaces or being bitten by infected rodents.

The disease has killed 65 Californians and some 600 Americans since hantavirus was identified in 1993, but it has never been known to be transmitted between humans.