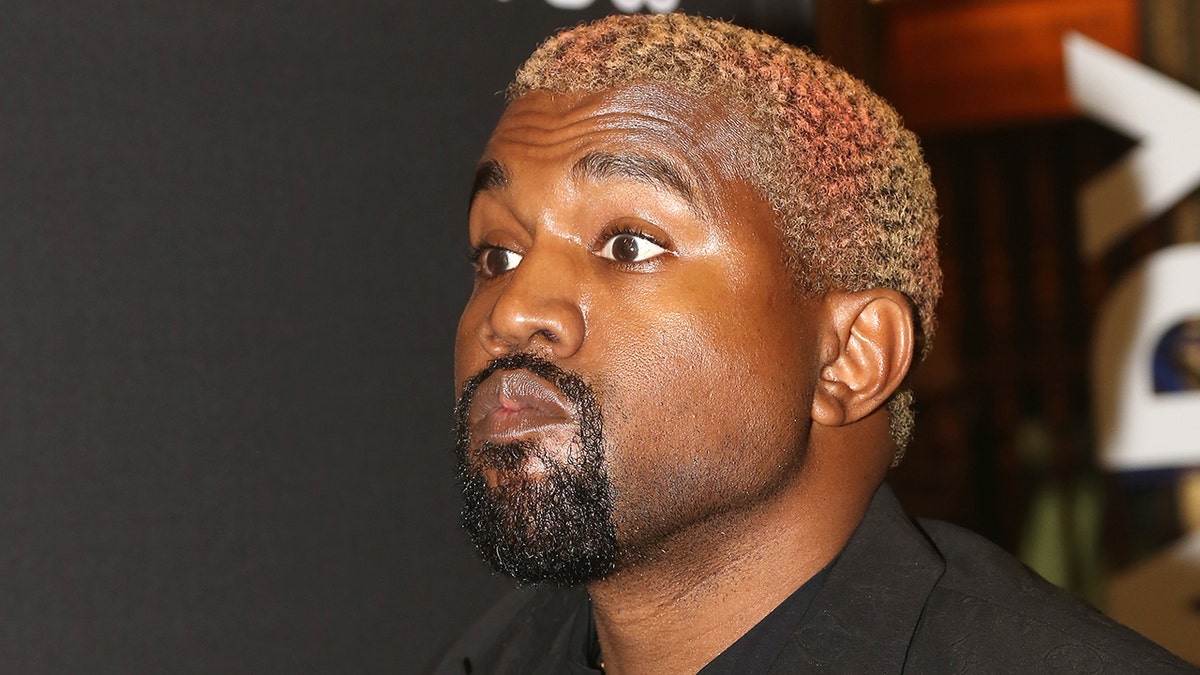

Kanye West's new contract makes it difficult for him to ever retire. (AP)

Slavery is not a term or a concept to be thrown around lightly. But if Kanye West’s statements last year about slavery being a choice were out of bounds, he’s taking more of a Prince-like tactic in his ongoing efforts to extract himself from his record and publishing contracts, as noted by The Hollywood Reporter. The publication points to a provision in his publishing contract with EMI — which was redacted from public viewing at the time the lawsuit was filed late in January but has been since revealed — that forbids him from not working.

“You (Mr. West) hereby represent and warrant that to [EMI] that You will, throughout the Term as extended by this Modification, remain actively involved in writing, recording and producing Compositions and Major Label Albums, as Your principle occupation. At no time during the Term will you seek to retire as a songwriter, recording artist or producer or take any extended hiatus during which you are not actively pursuing Your musical career in the same basic manner as You have pursued such career to date. (The preceding representation shall not be deemed to prevent You from taking a vacation of limited duration.)”

A music-publishing source tells Variety that such wording is common in publishing contracts, particularly for unproven songwriters. “The key phrase is ‘at no time during the term,'” the source says, “which is basically to say ‘We are about to give you a big advance, it’s not the time for you to decide to become a painter next week.’ He can do whatever he wants after the duration of the term.”

However, West’s contract with EMI (which is now owned by Sony/ATV Music Publishing) has been renewed several times, as noted in the lawsuit. His bid to be released from his publishing and recording deals revolves around a California law that limits personal-service contracts to no more than seven years. West claims that he’s been “laboring” for EMI since he first signed with the publisher in 2003.

“It makes no difference under [the relevant legal code] section 2855 whether the contract is otherwise fair, or whether the employer has fulfilled its end of the bargain,” his the complaint says. “It matters only whether the services began more than seven years ago. There can be no dispute that this happened here. The seven year period ended under this contract on October 1, 2010. For more than eight years thereafter — more than double the maximum seven year period California law allows — EMI has enforced rights in violation of California law, depriving Mr. West of the ‘breathing period’ that California law mandates.”

He also aims to prove that EMI was unfairly enriched by the West compositions it has published since October of 2010, and is seeking for the judge to declare that he is now the owner of those works. That claim means EMI can take the case from state to federal court, and it did so on Friday. While federal law allows copyright reversion, the option doesn’t come up until 35 years after a work is published — and chances are West is hoping to gain ownership of the works in question a lot sooner than that.