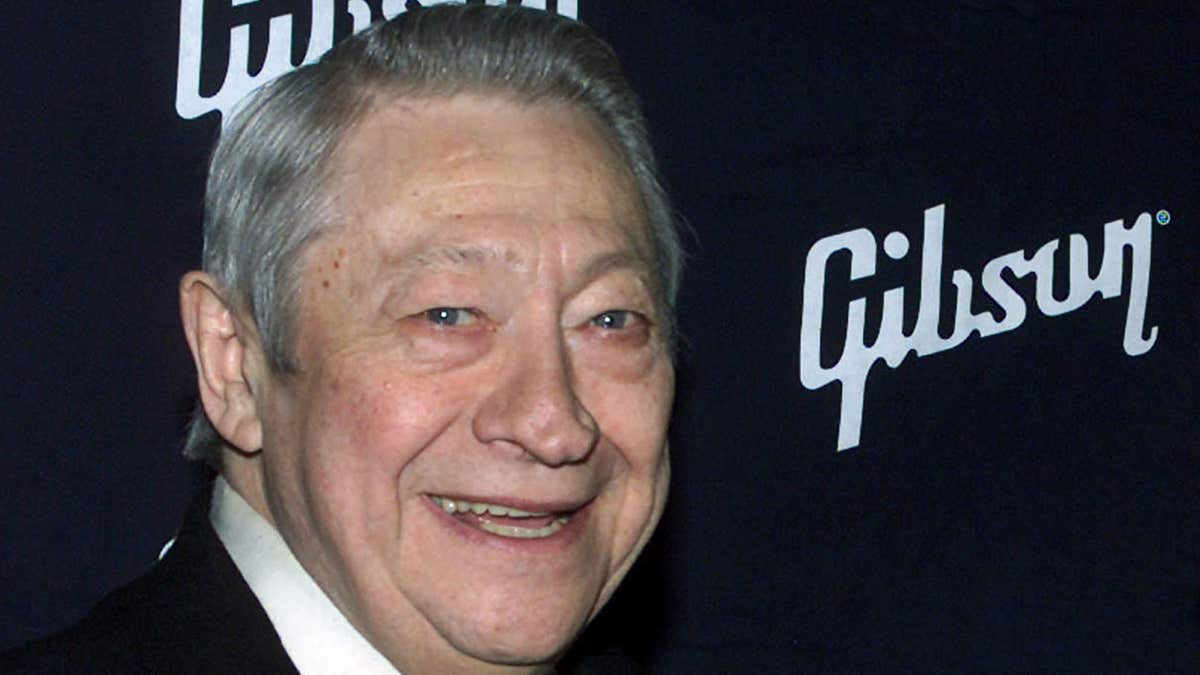

Feb. 26, 2002: Scotty Moore, who played guitar for the late Elvis Presley, poses in Hollywood. (Reuters)

NASHVILLE, Tenn. – Scotty Moore, the pioneering rock guitarist whose sharp, graceful style helped Elvis Presley shape his revolutionary sound and inspired a generation of musicians that included Keith Richards, Jimmy Page and Bruce Springsteen, died Tuesday. He was 84.

Moore died in his home in Nashville, biographer and friend James L. Dickerson said. Dickerson said a family member of Moore's longtime companion, Gail Pollock, who had been staying in the house with Moore confirmed the death. Pollock died in November 2015.

Moore, a member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, was the last survivor of a combo that included Presley, bassist Bill Black and producer Sam Phillips.

Moore was a local session musician when he and Black were thrown together with Presley on July 5, 1954 in the Memphis-based Sun Records studios. Presley was a self-effacing, but determined teen anxious to make a record. Moore's bright riffs and fluid solos — natural compliments to Presley's strumming rhythm guitar — and Black's hard-slapping work on a standup bass gave Elvis the foundation on which he developed a fresh blend of blues, gospel and country that came to be called rock 'n roll.

"One day, we went to have coffee with Sam and his secretary, Marion Keisker, and she was the one who brought up Elvis," Moore said in a 2014 interview with Guitar Player magazine. "We didn't know, but Marion had a crush on Elvis, and she asked Sam if he had ever talked to that boy who had been in there.

"Sam said to Marion, 'Go back in there and get that boy's telephone number, and give it to Scotty.' Then, Sam turned to me and said, 'Why don't you listen to this boy, and see what you think.' Marion came back with a slip of paper, and it said 'Elvis Presley.' I said, 'Elvis Presley — what the hell kind of a name is that?'"

For the now-legendary Sun sessions they covered a wide range of songs, from "That's All Right" to "Mystery Train." After "That's All Right" began drawing attention, Presley, Moore and Black took to the road playing any gig they could find, large or small, adding drummer D.J. Fontana and trying their best to be heard over thousands of screaming fans.

The hip-shaking Presley soon rose from regional act to superstardom, signing up with RCA Records and topping the charts with "Heartbreak Hotel," ''All Shook Up" and many other hits. Elvis was the star, but young musicians listened closely to Moore's contributions, whether the slow, churning solo he laid down on "Heartbreak Hotel" or the flashy lead on "Hard-Headed Woman."

"Everyone else wanted to be Elvis," Richards once observed. "I wanted to be Scotty."

Moore, Black and Fontana backed Presley for his shocking TV appearances and early movies, but by 1957 had tired of what Moore called "Elvis economics." In the memoir "That's Alright, Elvis," published in 1997, Moore noted that he earned just over $8,000 in 1956, while Presley became a millionaire. Moore also cited tension with Elvis' manager, "Colonel" Tom Parker.

"We couldn't go talk to Elvis and talk about anything," Moore, who along with Black left Presley's group, told The Tennessean newspaper in 1997. "There wasn't ever any privacy. It was designed that way, but not by Elvis. It's not that I feel bitterness, just disappointment."

Moore worked one more time with Elvis, for the 1968 "comeback" TV special that helped return him to the top of the charts. But Moore's compensation didn't even cover his travel expenses, he would recall, and he was not asked to join Presley's band for his tours in the 1970s. (Presley died in 1977).

Starting in the late 1950s, Moore worked on various projects. In 1959, singer Thomas Wayne had a Top 5 hit, "Tragedy," on Moore's Fernwood record label. Moore put out a solo album in 1964 called "The Guitar That Changed the World!" and with Fontana played on the 1997 Presley tribute album "All the King's Men," featuring Richards, Levon Helm and other stars. He and Fontana also backed Paul McCartney for the ex-Beatle's cover of "That's All Right." In 2000, Moore was inducted into the Rock Hall of Fame. More recently, he was a recording studio manager, engineer and businessman.

Moore was born near Gadsden, Tennessee, in 1931, and learned guitar at an early age. He was a fan of jazz and country and was strongly influenced by Chet Atkins and Les Paul. After serving in the Navy during World War II, he settled in Memphis, working at a dry cleaning plant during the day and playing music after his shift was over.

Phillips, who had not been impressed with Presley at first, had called in Moore and Black to work with the young singer. The two had been recorded by Phillips previously as members of a country-Western band, The Starlite Wranglers.

"I wanted them to get together (with Presley) and get a feel for each other," Phillips told the Los Angeles Times in 1981. "I also told them to keep an eye out for material."

Moore told of that recording session many times over the years, remembering that it was not going well until Presley broke into a spontaneous, upbeat version of "That's All Right." The song, also called "That's All Right, Mama," was originally recorded by bluesman Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup in 1946.

Moore and Black began jamming with Presley and helped work out the version that Phillips put on tape.

"Sam poked his head out of the door — this was before mixing consoles had a talkback button — and he said, 'What are you guys doing? That sounds pretty good. Why don't you keep doing it,'" Moore told Guitar Player. "So I got my guitar, ran through it a couple of times, and that was it. That was the beginning of, how do you say it — all hell breaking loose!"